Stand in the Kaufmann House living room and you’ll understand why Richard Neutra made grown architects cry. The desert doesn’t stop at the glass — it flows through the house like wind. This wasn’t decoration. It was revolution, one sliding glass wall at a time.

The Viennese Who Reimagined America

Richard Neutra arrived in America in 1923 with impeccable timing and impossible dreams. Born in Vienna in 1892, he’d studied under Adolf Loos (who famously declared ornament a crime) and worked with Erich Mendelsohn in Berlin. But Europe felt heavy with history. California promised virgin territory for radical ideas.

His first LA moment came in 1925, working briefly with Frank Lloyd Wright on the Imperial Hotel drawings. But Neutra wasn’t interested in Wright’s romantic Prairie Style. He wanted something harder, cleaner — architecture that captured the nerve of modern life. By 1927, he’d designed the Lovell Health House, and American architecture would never recover.

- Born: April 8, 1892, Vienna, Austria

- Arrived in US: 1923 (became citizen 1929)

- Died: April 16, 1970, Wuppertal, Germany

- Buildings designed: 300+ (about 90 survive)

- Revolutionary weapon: The sliding glass door

The Neutra Formula: Biology Meets Steel

Neutra called it “biorealism” — designing for human nervous systems, not architectural magazines. He obsessed over sight lines, studying how eyes track through space. His houses don’t have views; they choreograph them. Turn a corner, and suddenly the Pacific Ocean fills your vision. Sit on his built-in couches, and mountains frame themselves perfectly in steel mullions.

The magic happened through subtraction. While others added details, Neutra removed barriers. His “spider leg” outriggers — thin steel beams supporting impossible cantilevers — let roofs float. Walls became suggestions. Inside and outside merged until clients forgot which was which.

The Elements That Define Neutra

- Post-and-beam construction: Steel or wood frames that freed walls from load-bearing duty

- Sliding glass walls: Not windows — entire walls that vanished into pockets

- Reflecting pools: Water as architecture, doubling space and light

- Built-in everything: Sofas, desks, and shelves that made furniture obsolete

- Horizontal emphasis: Roofs that stretched beyond walls, grounding buildings to landscape

The Houses That Changed Everything

Lovell Health House (1929)

Perched on a Hollywood hillside like a three-story skeleton, the Lovell House announced Neutra’s arrival with steel fanfare. Dr. Philip Lovell, naturopath and health columnist, wanted a house that embodied his “physical culture” philosophy. Neutra delivered America’s first steel-frame residence — assembled in 40 hours after prefabrication.

The neighbors were horrified. The architecture establishment was electrified. Here was a house that looked like it arrived from 1960, built when Model T’s still ruled the roads. Today, it’s a private residence (no tours), but you can glimpse it from Dundee Drive — still shocking after 95 years.

Kaufmann House (1946)

Edgar Kaufmann had already commissioned Fallingwater from Frank Lloyd Wright. For his Palm Springs winter house, he wanted the opposite — not romance but precision. Neutra gave him a 3,200-square-foot horizontal machine that made the desert feel air-conditioned.

The innovation? “Pinwheel” plan with wings radiating from a central core, each capturing different views and breezes. The famous Slim Aarons photograph — glamorous people lounging by the pool with mountains beyond — became the image of Palm Springs modernism. Restored meticulously, it’s now open for tours during Modernism Week ($150, book months ahead).

Case Study House #20 (1948)

For John Entenza’s experimental program, Neutra created a 2,300-square-foot demonstration of postwar possibility. The Bailey House (as it’s known) cost just $12,000 in 1948 — proving great design didn’t require Kaufmann money. Its trick? Standardized components arranged brilliantly, like Beethoven using the same 88 piano keys as everyone else.

Still privately owned in Pacific Palisades, it influenced thousands of tract houses — though few builders understood that copying the flat roof while ignoring the proportions missed the entire point.

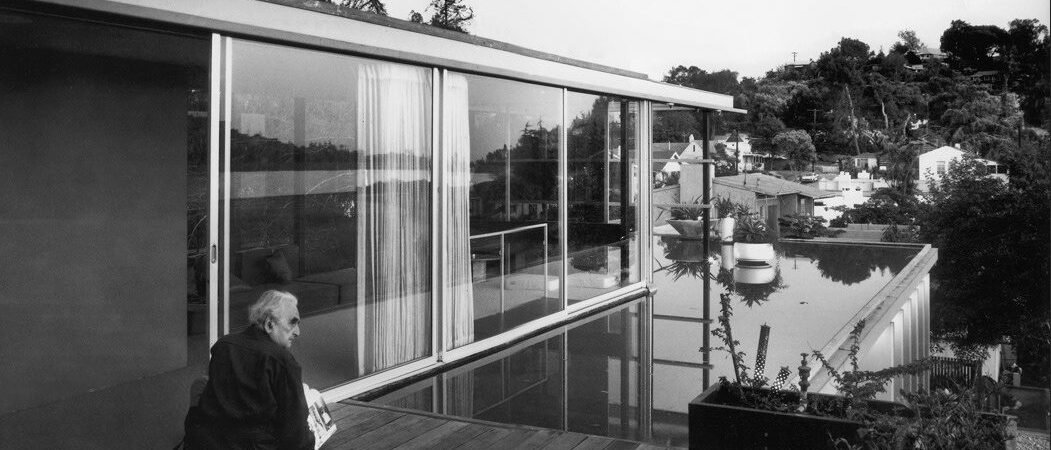

The VDL House: Neutra’s Own Laboratory

Want to understand Neutra? Visit his own house. The VDL Research House in Silver Lake wasn’t just home — it was a manifesto you could sleep in. Named for patron Cees H. Van Der Leeuw, it demonstrated every Neutra principle on a tight city lot.

After fire destroyed it in 1963, Neutra (then 71) rebuilt with son Dion — making it even more radical. The new version featured a roof pond that cooled the house and reflected sky into every room. Today, Cal Poly Pomona runs it as a house museum. Saturday tours ($10) let you experience Neutra’s daily life — from the bathroom where mirrors create infinity to the penthouse where LA spreads like a circuit board.

- Address: 2300 Silver Lake Blvd, LA 90039

- Tours: Saturdays 11am-3pm

- Pro tip: The docents are architecture students who geek out properly

- Best detail: Kitchen cabinets that disappear completely when closed

Neutra’s Design Philosophy Decoded

Nature as Co-Architect

Neutra didn’t build in landscapes — he collaborated with them. His houses frame specific views like cinema directors. The Singleton House positions its dining table so sunset hits your salad at exactly the right angle in June. This wasn’t accident but calculation, using sun charts and view studies that filled notebooks.

The Therapeutic Environment

Having survived World War I and Spanish flu, Neutra believed architecture could heal. His “health houses” prescribed natural light like medicine, cross-ventilation like therapy. He’d quiz clients about their anxieties, then design spaces to calm specific nervous conditions. Claustrophobic? Here’s a corner that opens three directions.

Machine Aesthetics, Human Touch

While Corbusier called houses “machines for living,” Neutra made machines that felt human. His details — rounded corners where shoulders might bump, built-in desks at perfect writing height — showed obsessive attention to bodies in space. He’d visit completed houses to watch how people actually lived, adjusting future designs accordingly.

Finding Neutra Today: A Pilgrim’s Guide

Los Angeles Area

- VDL House: Only regular public access (Silver Lake)

- Lovell Health House: Private, view from Dundee Drive

- Strathmore Apartments: Drive-by viewing welcomed (Westwood)

- Neutra Office Building: 2379 Glendale Blvd (still operating)

Palm Springs

- Kaufmann House: Tours during Modernism Week

- Miller House: Occasionally open for tours

- Maslon House: Demolished 2002 (weep here)

Beyond California

- Pitcairn House: Pennsylvania (private)

- Bewobau Houses: Germany (Quickborn)

- Painted Desert Community: Arizona (drive through)

The Neutra Effect on Modern Living

Every sliding glass door in every suburban house owes a debt to Neutra. He didn’t invent the technology, but he showed America why it mattered. Before Neutra, windows were holes punched in walls. After Neutra, walls themselves could vanish.

His influence spreads beyond architecture. The Apple Store’s transparency? Neutra. The indoor-outdoor restaurant trend? Neutra. The millennial obsession with natural light? Neutra proved its value when Eisenhower was president.

But copies miss the philosophy. Neutra’s spaces work because every decision serves human experience. The pool reflects morning light onto bedroom ceilings, waking residents gently. Kitchen windows frame herb gardens at counter height. These aren’t accidents but acts of care.

Why Neutra Matters Now

In an age of work-from-home and screen fatigue, Neutra’s biorealism feels prophetic. He understood that humans need connection to nature, that light affects mood, that space shapes behavior. His 1950s clients wanted the same things we do: calm, clarity, and California sunshine.

The tragedy? We’ve built millions of houses with Neutra-inspired elements but Neutra-opposed spirits. Flat roofs without proper drainage. Glass walls facing west without overhangs. Open plans that feel exposed rather than expansive. We copied the look but missed the logic.

Visit a real Neutra house and you’ll understand. They’re not just beautiful — they’re intelligent. They know where the sun rises, how breezes flow, what makes humans feel safe yet free. In a world of Instagram architecture, Neutra reminds us that the best design disappears, leaving only life, beautifully framed.